FELIPE OLIVEIRA BAPTISTA

SANDRA NOBRE

Words

ERICK FAULKNER

Photography

Felipe Oliveira Baptista (born 1975) conquered Paris as a fashion designer, initially under his own name, before he became creative director for a number of iconic brands, such as Lacoste and Kenzo. In the summer of 2021, when the brand founded by Japanese Kenzo Takada wanted to change their strategy, he decided to part ways. Upon leaving, he began mapping out his path for the following three years, the time he gave himself to explore other creative endeavours. He returned to Lisbon, where he lived before moving to study in the French capital, immersing himself in painting and photography, areas he was already familiar with. His restless gaze persists. Recently reinstalled in his Parisian flat, which overlooks Montmartre and Sacré-Coeur, with his wife, Séverine, they set up a studio for each one to focus on new projects. Life is different but he doesn’t exclude the possibility of returning to the passerelles, because he still has lots to say.

“THE WAY I PROTECT MYSELF FROM WHAT’S HAPPENING IN THE WORLD IS TO BE ALWAYS CREATING; JUST BEING A SPECTATOR IS PARALYSING.”

What was it like returning to Lisbon after all these years?

I didn’t think I would notice such a difference. I visited Lisbon three or four times a year and had the idea that it was very open, with the tourism and the arrival of foreigners. From the outside, the city seemed to have great energy. There was the initial moment, living with all that light once more, with the architecture, being back with old friends and family. I thought it would be easy to blend with people with different horizons. However, I found a very divided city, the Portuguese with the Portuguese, the foreigners with the foreigners, even in creative areas, those in fashion with those in fashion... Also, it’s obvious that it’s lost much of its authenticity. Saying that, it meant I had a long period of time to reflect and create, which I was unaccustomed to, due to the relentless nature of the fashion calendar.

What time did you find?

Time to be able to think about and work on new projects. To sow seeds for new ideas, which was very interesting. After 20 years of working intensively, my wife and I decided that there were other creative areas and activities we can explore. Leaving the Paris environment helped everything get off the ground.

What was the creative impulse?

I was used to working with teams of 40 people coming up with ideas, various off-shoots and teamwork. That was the most difficult part. I’m a very impatient person by nature and I like movement. The first year was one of adaptation. Once I established my pace and realised what I liked doing, it became easier. In Paris, I always have a choice, while in Lisbon I have to search and wait for new stuff, which is still stimulating because it pushes us. It was a creative retreat, in a way.

Did this allow you to hear your inner voice?

Exactly, it established an interior conversation. I’m lucky enough to have always worked with Séverine and we talk a lot. She also took a break to do other projects – since then, she has focussed on interior design. Each one started a new chapter. But the conversation was more introspective. Many things I started to create are based on previous work, ideas that I had kept... I’ve yet to explore most of the things in my head. It was like detoxing adrenaline. Like a journalist told me, fashion is a hard drug, and truth be told, there’s that excitement about starting a collection and finishing it in six months, which ends up creating rhythms and habits that stunts creativity.

During this period, after designing a dress for an artwork by Julião Sarmento, which is part of the CAM collection (Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation), your artistic streak was particularly strong in painting and photography.

Yes, I was involved in the Sète Contemporary Art Festival, [a partnership between Portugal and France, showcasing the work of 28 artists, between Lisbon, Almada, and Sète], at the Capuchos Convent in Caparica. The collective exhibition took place inside the museum, but I wanted to do it in the cloisters and viewpoint. I installed three large slates and, every day of the festival, I did a new drawing, which would be erased to make space for the next. This performance inspired a film by Joana Lourenço, which was shown at Leffest [Lisbon Film Festival], which was a remarkable experience.

At that edition, you were also part of the selection jury at Leffest, where many big names in cinema had been.

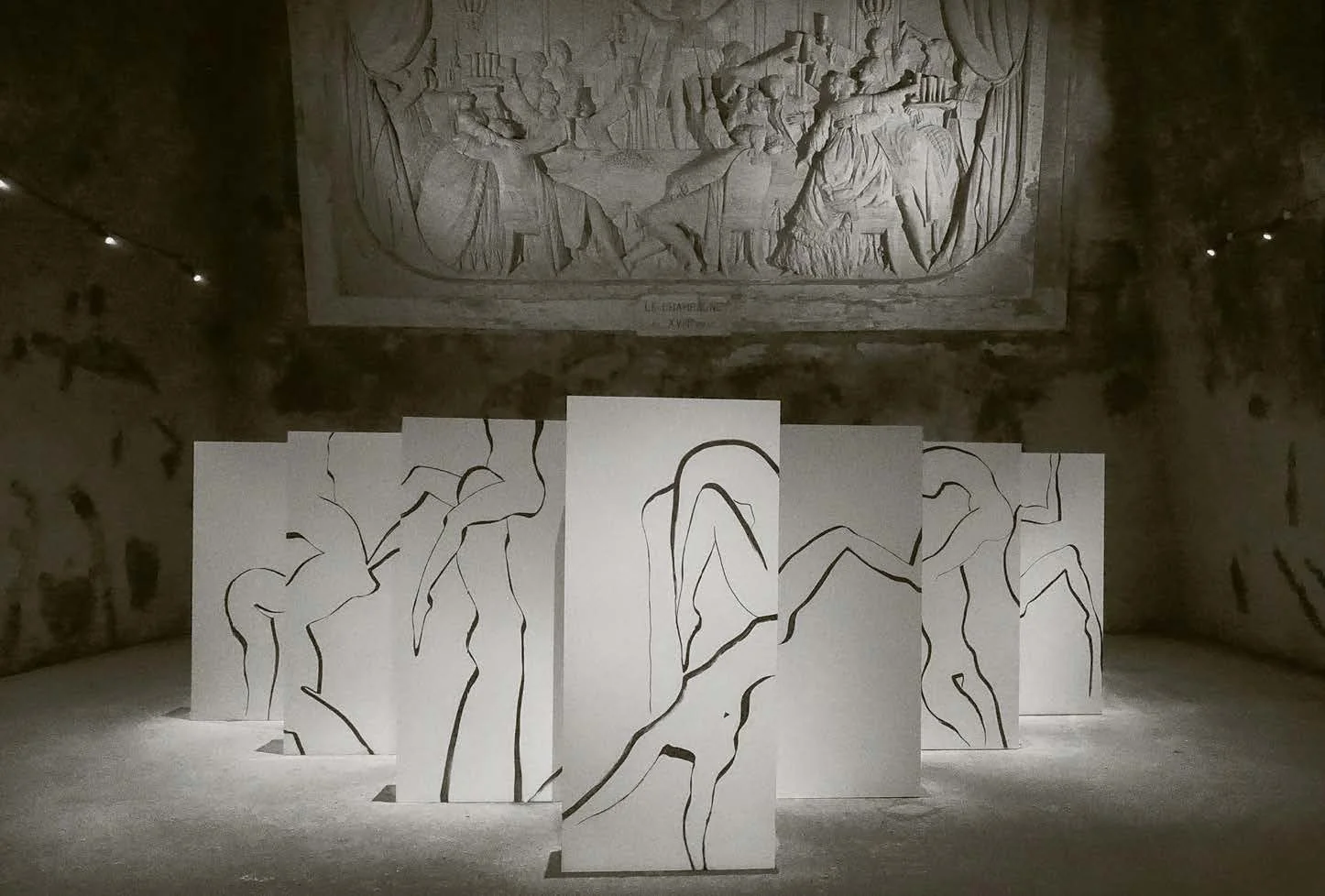

I love cinema! It has always inspired me and it inspires me in my work. That week, in November of last year, was incredible, because, for me, watching three of four films a day is a dream. The film selection, the people, it was really interesting. From that came an exhibition in Sète and another currently on show in France. I started doing large formats of my photographs, and I have other embryonic projects... like Awe, which is a series of images that address different and conflicting emotions, where I explore the emotional and intuitive sides rather than a concept, which I hope will be shown soon. In the meantime, another exhibition was supposed to end in the Champagne-Pommery cellars, in Reims, which is an amazing space with two kilometres of underground passages, which includes a video by Patti Smith and the Soundwalk Collective, and various other artists. I did a mural that’s almost 40 metres long. The exhibition was well received and was extended until March.

What’s the message? What do you want to say via photography and painting?

To a certain point, that’s yet to be discovered. What they have in common with fashion is emotional exploration, sparking conversations. For example, my drawing focusses on the body and liberating the body, in photography it’s more abstract, the idea is to move away from the narrative. It’s not as if I don’t have a message, I want to have one, but I don’t want to pontificate. It’s about allowing openness of thought. I like seeing contrary reactions to the work. There’s a humanistic aspect that’s common to all three fields, be it clothing, drawings, or images. Fashion has turned into an industry that overproduces; it’s interesting to refine the message, to make it quieter. I prefer a less materialistic, more experiential approach. I didn’t want to leave one system to enter another, as such, the new projects have been more intuitive.

“my drawing focusses on the body and liberating the body”

In this process of rebirth, as an artist, do you still get invitations to work?

In terms of art, invitations are much rarer, even in Paris. People are reticent when it comes to those coming from other fields. It’s like being 20 and having to start a career. That said, the work has to speak louder than my career. I started taking photographs and drawing well before I started working in fashion; I had my first camera at the age of 12. When working as a creative director, I implemented a vision that involved an intersection of many artistic expressions. The path isn’t a perfect, straight line, thankfully, otherwise it would be very dull. Creatively, I wonder about my work; I don’t think I know everything or that I’m at a safe level. I know what I know, what I’ve done, and what I’ve learned. Even so, I continue doing these mental gymnastics and work on them. During this process, people’s perspective changes, not my creation, and people love a label that’s easy to understand; for me, what horrifies me most are labels.

You need some humility to exhibit in a new field and open yourself up to criticism.

Humility, yes, but most of all, courage to abandon the comfort of a status and position to achieve another, where you won’t have the same acceptance, which is normal. I haven’t proved anything, so I don’t get upset by any reaction from a curator or gallery owner. Every criticism has guidance that can help me move forward. Saying that, I don’t expect to reach the same level as fashion. It’s like square one, doing a reset.

After these three years, is there a plan for the future?

The plan is to continue moving ahead and undertake projects, and if something in fashion comes up, everything else will move onto standby.

Does that mean that you’re not excluding the possibility of going back to fashion?

This year, I did a book, which consisted of a retrospective of the three main parts of my work in fashion — with my own brand, with Lacoste and with Kenzo. It was like creative therapy to see if I wanted to return, to see if I still have something say. I felt the desire to work in fashion again. Truth be told, I miss the teamwork, the rush, the pressure.

“Fashion has become something more of a pop event, where it’s more about who goes than the clothes themselves. The world of luxury itself is being redefined; it’s the end of a cycle.”

Did you get any proposals to return?

Yes, invitations to work in fashion continue to arrive, but it has to be something interesting, where I feel I can develop my work, where I’ll continue to learn and grow, giving that to a brand. It has to be a combination of a good project and a good company, as well as management that has a clear idea of what it wants to do. I almost went to Italy last year, but I’m open to challenges.

How do you see the role of the artist in the current global context?

We’re living in a completely insane period. As an artist, the way I protect myself from what’s happening in the world is to be always creating; just being a spectator is paralysing. We feel impotent. I have to express myself, but I also understand that not all art has a political vocation. A positive and humanist message can give hope, and that, in itself, is a political act. I would love to be part of the solution and not the problem. If I can do something that helps or inspires others, I will. It’s a challenge, not only with regard to what to say, but also how to say it and when to say it. We lack time to digest everything. Lisbon allowed me to do so.

What moves you in art?

For example, I spent three days at the Les Recontres d’Arles festival, with exhibitions throughout the city. I started with a work by Nan Goldin, shown at a church, which involved a slideshow with photos of statues from a variety of museums and people, in a mythological play, with incredible music. All this at nine in the morning. Almost a sacred moment. Seeing such personal and extraordinary work inspires me. This is what makes me live and breathe art.

Does the ephemeral scare you? For example, creative directors at fashion houses changing regularly.

Absolutely. It’s like hyperbolic fast pop culture. A few years ago, I remember telling a journalist friend of mine that, in the future, we would be like football players playing seasons for different brands, which is already happening at a mad pace. I spent eight years at Lacoste and three at Kenzo. If in eight years there’s time to say things, to leave a mark, in three, there was a great promise and three beautiful fashion shows, but there was a lack of substance. Therefore, when they wanted to go back to being a sportswear brand, I decided to leave by mutual agreement. Fashion has become something more of a pop event, where it’s more about who goes than the clothes themselves. The world of luxury itself is being redefined; it’s the end of a cycle. People will always need to buy clothes, but whether it’s for quality or a brand with a logo, we shall see.

What place does the Azores hold in your life?

It’s the place I was born, where I return almost every year. I’ve never lived in the Azores, I grew up in Lisbon, but my childhood memories are in the Azores, where I spent the summer holidays. Much of my work is connected to that root.

Is it a type of time capsule, where people live at a different pace?

Distance has preserved the islands greatly. On one of the more recent trips, I took my children to São Miguel, one of the most photogenic islands, to see the lagoons with incredible colours, the blue and green. People would take a selfie and get back in the car, almost not seeing anything... That’s how we live, nowadays. For me, it’s still a haven, there’s a sense of belonging. I think that the way I see the world, what I look for in shapes, even the silence is all connected to the Azores. When you’re on an island, in the middle of the ocean, there’s a certain humility, which becomes ingrained. An island is something very magical to me. I was very lucky to have been born somewhere so special.